George told me. ‘Me grand-uncle was in Monaghan gaol for a debt of eleven shillings. Me granny brought him his dinner of champ every day. Twenty one and a half Irish miles to Monaghan, she’d have the champ warm enough to melt the butter.’

The Green Fool, Patrick Kavanagh

Champ, also known as cally, brúitín, poundies, stelk, or thump (when made with beef), is a traditional Irish dish that is essentially seasoned, buttered mashed potatoes. Potatoes, usually in large amounts, were boiled, then drained, mashed, and seasoned with greens simmered in milk or cream. The hot mixture was served with a knob of butter in the middle, into which each spoon or forkful could be dipped. Often associated with peasants or farmers, and thought to have emerged as an inexpensive staple dish once the potato mono-culture took root, champ has been elevated to a trendy, even sophisticated version of a much-loved comfort food.

“No Irish country woman dreams of serving meat with champ. Good country butter to eat with it and buttermilk to drink is all she thinks necessary….No Irish cook will have any difficulty in making good dishes with champ once she gets the idea of champ not being the only thing required for dinner” (Northern Whig, 6 March 1943).

The origin of the word “champ” is not known, but it seems that most agree it’s a Scottish term related to “quagmire,” or even one similar to the English word, “to crush.” This Ulster-Scots background would make sense geographically with the dish’s popularity in Northern Ireland. “Poundies” is more obvious, coming from the way in which the potatoes are whacked with an old-fashioned potato masher, a wooden “beetle.”

“Brúitín” is less clear. The Irish Times‘ “The Words We Use” gives this definition:

“Mary Kenny from Malahide has been reading Peter Carey’s fine novel True History of the Kelly Gang which won the Booker Prize recently. She asks for information about some words used by Ned Kelly. The first is bruitin. I quote: “Aunt Kate . . . made what my father called bruitin and the Quinns champ it is potatoes mashed up with a great lump of butter.” The Irish is br·it∅n, related to br·, to press, mash.”

A more interesting version is found in the Strabane Weekly News (26 August 1911):

“I should perhaps explain that it is derived from the Greek word “New-spuds-beetled” — accent on the “beetled.” We have here a clear illustration of how a word may be corrupted; originally beetled spuds were used in the manufacture of that most toothsome of dainties known as “Boxty.” The following lines from the classical poets touch on the matter: —The boxty mills began to shill, You’d think it was a fiddle, O; She rolled it up in her coat-tail And baked it on the griddle, O. It seems pretty clear that the use of boxty was restricted to the “upper ten” in the middle ages, and was finally discarded altogether, owing to the difficulty in getting rid of the “juke-the-beetles,” and at what time the bottom of a tin porringer was introduced for the purpose of bruising boiled spuds is not known with any degree of certainty; it is clear, however, that the term “bruitin” came into use at the same period, inasmuch as potatoes from that time forward were “bruised with a tin,” usage shortening the word down to “bruitin,” a contraction of the first and last words of the phrase.”

A reference to “bruitin” is also found in the same paper on 22 April 1899, in an article describing a case brought by Mrs. Hannah McQuaid of Dooish against Robert Bradley for slander, when he “circulated a report to the effect that she sold butter in this market with bruised potatoes in the centre of the miscaun.”: “There were churning at the time and he told them to not do as they did at Dooish market — put “bruitin” in the butter.” “He never got anything in the butter but butter itself. He never got “bruitin” or potatoes in butter in his life.”

“The man of the house was summoned when all was ready, and while he pounded this enormous potful of potatoes with a sturdy wooden beetle, his wife added the potful of milk and nettles, or scallions, or chives, or parsley and he beetled it ’till it was as smooth as butter, not a lump anywhere. Everyone got a large bowlful, made a hole in the centre, and into this put a large lump of butter. Then, the champ was eaten from the outside with a spoon or fork, dipping it into the melted butter in the centre.” – Florence Irwin, Irish Country Recipes (1937)

“When potatoes are beginning to get bad the people make what is called “champ” The Irish mother was particularly good at making “Champ”. This is the way the people make “champ”. They peel the potatoes and wash them: and put them in a pot and put water on them. When they are done they drain the water of them. Then they put salt on them and pound them with a “beetle”. Then they put a measure of milk on them and pound them again.” – Lecklevera, Co. Monaghan (NFCS 0950:522)

“Throw the Beetle at Her” is also a traditional slip jig.

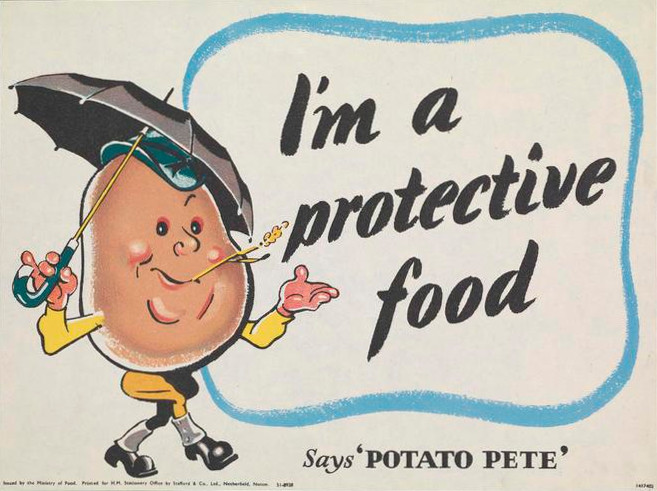

Champ featured into the UK’s WWII bread rationing scheme, as illustrated in a January 13 1943 report by the Belfast Telegraph. Minister of Food Lord Woolton delivered an “Eat More Potatoes” speech during a Northern Ireland campaign that saw “150 volunteer lecturers and demonstrators throughout the country” “give instruction on the use of potatoes.” It highlighted Ulster bakers’ centuries-long “use of potatoes in pastries,” including speciality flours and confectionaries, “for generations.” The mascot, with which a chocolate tart was made, was “Potato Pete,” described as an “immense potato in hat and spats with a potato fork over his shoulder and a straw in his mouth.” “Just to look at him makes you think of all the things he stands for — like potato fadge and potato cakes and champ and dumplings and a dozen other things that make your teeth water.”

Ingredients

POTATOES

“A sumptuous Irish boiled potato, the stuff of our dreams, is a ‘ball of flour.’ Its taut jacket, just cracked, curls open to release the steam. Inside, it is parched, crying out thirstily for lashings of butter to melt into it, to moisten its fluffy centre and crown it with a salty deposit.”

Sunday Tribune 5 Oct 1997

The best potatoes for this recipe are floury potatoes, which have a low water and sugar content but are high in starch. They are dry and fluffy, making them ideal for mashing and frying. When it’s time for the new potatoes of the season, which have a lower crop yield, to hit the market, only the best are labeled “balls of flour.”

“There is a certain amount of thrill and pride about digging out the first of the new ones. It is either an excellent crop or a mass of “marbles.” In any event you always tell the neighbour that you have “been digging”, that it’s a very good crop and “all balls of flour.” You never forget the “balls of flour” part even though we all know, including the neighbour, that they are wet and soapy.”

Drogheda Argus and Leinster Journal 5 July 1974

The most popular floury potatoes, which are the type of potato preferred by Irish consumers, are the Rooster (60% of all sold, according to the Irish Potato Federation), Kerr’s Pink (5%), Golden Wonder (5%), Records, and Queens. The Russet would be the US equivalent in popularity of a floury American potato, which can be used here.

Random but fun fact: Potoooooooo (Pot-8-Os) was a championship racehorse in 18th-century England. According to legend, his owner Willoughby Bertie told the stable boy to write the horse’s name, “Potato,” on his feed bin, and he took that literally and phonetically, “Pot – O – O – O – O – O – O – O – O” (Pot Eight Os). Bertie liked it so much he kept the name.

SCALLIONS

Any green vegetable can, and was, used to flavor the potatoes, and although one proved to be more popular than the others, nettles, parsley, chives, and even peas and dulse are commonly seen in champ recipes. When cooked, the sting of the nettle tops would be removed.

Scallions, green onions or spring onions, are related to onions, shallots, leeks, and chives. They’re often served raw in Asian dishes and salads, but are simmered to release their full flavor in champ. You can cook the whole onion – it’s up to you whether or not you’d like to separate the lower white part from the green top, which can be used as a garnish.

Folklore

When searching Duchas, champ is described as an “older” food, often eaten with oat cakes and in the summer or taken or served to those partaking in manual labor.

In Donegal transcripts, this dish is usually called poundies or brúitín, although the terminology is not exclusive to that county. It is almost always referenced in the context of feast days, specifically Halloween (All Hallow’s Eve, Samhain, All) and St. Brigid’s Day.

On Hallow Eve, after the house was cleaned, a dish of champ was left out for the souls of the dead on the table or hob. Spoons were placed in them as well, and if they were moved, that was taken as a sign, either of a birth or a death depending on the region. There were also some more serious consequences:

“Mashed potatoes locally called “Champ” was always eaten at Hallow – Eve; and anybody who happened to sneeze while eating it was supposed to die within the year.” – James Daly, Greaghnaroog, Co. Monaghan (NFCS 0933:294)

“The first mouthful of champ you eat on Hallow Eve night run to three doors and who ever the people in the house of the third door is talking about is the person who is supposed to be your future husband.” – Tressa Ní Conchbhair, Rampark, Co. Louth (NFCS 0660:314)

On St. Brigid’s Day, champ is traditionally eaten but also surrounded by the customary rush crosses that are hand made for the occasion.

“Sé seo cuid de na nosannai atá ag na daoine thart fa seo ar na féili. An céad ceann Lá Fhéil Brighde. Siad na nosannaí a bhíos aca an lá sin bionn bruitín aca ag an dinnéar. Ins an tráthnóna a bíos an dinnear aca an lá sin. Bíonn arán coirce leis an bruitín fosta. Annsin nuair a bíonn an bruitín thart téigheann fear an toighe amach agus bainn sé na feaghacha agus ag tuitim na h-oidhche na h-oidhche ma bhionn cailín sa teaghlach darbh’ainm Brighid téigheann sí amach agus tógann sí na fiaghacha agus deiridh sí taobh amuigh de ‘n doras “Téidhigig ar bhur nglúnaibh fosglagaidh bhur súile agus leigigidh Brighid isteach”. Deireann na daoine taobh istuigh “sé do Bheatha” agus deirtear sin trí theit. Fágtar brat dearg taobh amuigh os ceann an doras an oidhche sin fósta agus ghní siad crosannaí de na fiaghacha.” – Cáit Bean Uí Bhuidhe, Kill, Co. Donegal (NFCS 1080:153)

“On St. Brigid’s Day we gather rushes and on that night we make “poundies”. When you are making them you peel the potatoes first. Then you boil them and put a cut onion in them. After that they are champed and everyone gets a bowl full of them. Then they eat them with milk and butter. You leave the rushes on the door step until night and then somebody goes out for them. The person that goes out knocks and says. “Gabhaigidh bhur nglúna agus fosgailí bhur súile agus leigigidh isteach Bhrígid bhig bhéannacht”. The person inside says “Sé do bheatha a mná uaisle. Then they spread the rushes on the table and eat the “poundies”.” – G. Mullen, Portnablahy, Co. Donegal (NFCS 1077:49)

“Ar oidhche fhéil Brighdhe í gchomhnuidhe bhéadh brúitín ag na daoine, seo e an dóigh leis an brúitín a dhéanamh. Bhéirfeadh na daoine leobhtha tobán préataí agus iad a nigh agus an crochan a bhaint daobhtha, agus iad a nigh í dtrí uisge agus an pota a nigh fosta agus iad a chuir síos agus nuair a bhéadh siad bruithte iad a bhruigheadh agus nuair a bhéadh siad leath bruighte báinne a chur isteach ortha agus iad a bhruigheadh aráis. Nuair a bhéadh siad bruighte annsin cupla soitheach brúithin a bhaint amach as an pota fá choinne na fír agus fód mór ime í na lár agus spanóg ag achan duine (achan) aca agus nuair atá na fír ag ithe bhíonn cochan aca faoí’n tabla san am chéadna agus fágtar amuigh cleibh brátogaí fosta agus bíonn báll le achan duine sa cleibh bheirtear isteach an cleibh annsin agus toiseochaimidh ag déanamh croiseóga dé’n cochan agus nuair atá an oidhche sin thart chaiteann muid an brátóg sin go cionn bliadhna arais.” – Siubhan Ní Dhochartaigh, Meenderryherk Glebe, Co. Donegal (NFCS 1057:443)

“There was a man one time, and on Saint Brigid’s night he went out to cut rushes to make crosses. When he was going out, the poundies had been taken of to be pounded. When he was out in the field, he heard the faries calling “Give me a horse, give me a horse”, and the man said also “give me a horse.” He got on a nice white horse, and after a long journey he reached a place that he thought was Malin head, and he was taken to a castle, and he was treated well. When he came out he got on the horse’s back again, and he reached another castle the same kind, and he was treated well there also. When he came out he got on the horse’s back, and before long he was back in the field. When he reached home they had not the poundies pounded. The two castles that he saw were fairies castles.” – Rashenny, Co. Donegal (NFCS 1122:143)

Another traditional time champ was eaten was on Fridays (“Champ is still used on Fridays with a hole in the centre for butter” NFCS 0933:222).

“New potatoes are nicely peeled by rubbing them when washed with a clean coarse brush. The potatoes are teemed and then pounded with a clean pounder. To this is added sweet milk and still pounded and newly cut tops of onions are mixed through it. This is taken for dinner with butter on Fridays.” – Larah, Co. Cavan (NFCS 0981:112)

There were also several references to rings being put in champ, and finding it being a sign of marriage, as well as coins.

A saying I saw a few times but still do not understand is “Champ to champ would choke you.”

A popular old riddle:

How many potatoes makes Bruitin?

As many as you have butter for

Bonus:

Riddle me, riddle, me, “ruitin”, how many potatoes in a pot of “bruitin”?

None because they are all “Cruitin”. (NFCS 0205:016)

Champ Recipe

From Darina Allen’s Irish Traditional Cooking – serves 4.

INGREDIENTS

6-8 floury potatoes

1 bunch scallions

360ml / 1 ½ cups milk

60g-120g / 4-8 tablespoons butter

salt and pepper

optional: cheese

METHOD

1. Scrub potatoes and boil.

2. Finely chop scallions. Cover with cold milk and bring to a boil.

3. Simmer for 3 to 4 minutes, remove from heat and let infuse.

4. Peel and mash potatoes. Mix hot with scallions and milk.

5. Beat in some butter and season to taste with salt and pepper.

7. Serve in with a knob of butter melting in the center.

Note: Champ may be reheated, covered in foil, at 350°F/180°C.