The mention of caraway seeds, for many, immediately brings to mind soda bread. It is uniquely associated with Ireland in that sense, but it is also the star of the once-ubiquitous seed cake or carvie cake, a lesser known baked good that was a common sight during tea time.

Caraway (Carum carvi) is a biennial herb native to Europe, Asia, and North Africa, in the same family as carrots and parsley. The common belief is that the use of caraway seeds is attributed to the ancient Arabs, although remnants that are thousands of years old have been found at lake dwellings in Switzerland. It was documented by the ancient Romans and Greeks before it made its way to mainland Europe, where it is considered one of the oldest spices. It appeared in Shakespeare’s Henry IV, and featured in folklore as a protective talisman against witchcraft, thievery, and erring lovers.

While food author and historian Michael Krondl calls it “a cheap peasant spice,” its popularity has endured. Caraway is used heavily in German and Austrian dishes, as well as in Eastern European and North African cuisine. In Mary F. Wack’s “Recipe-Collecting, Embodied Imagination, and Transatlantic Connections in an Irish Emigrant’s Cooking” she calls caraway a “secondary Irish and Ulster flavour principle,” a concept also supported by Máirtín Mac Con Iomaire in “Recognizing Food As Part of Ireland’s Intangible Cultural Heritage.” It is a primary component in Scandinavian aquavit and German kümmel. Today, Holland is the largest producer of caraway. While caraway seeds were used to treat stomach ailments and aid digestion in 19th century rural Ireland, their medicinal value was noted in the Ebers Papyrus (1550 BC) as well as in the writings of Hildegard.

Seed cake is a very old cake, with British origins, but nonetheless extremely popular in Wales and in Ireland, where caraway seeds have been seen from the 16th century onward. The “seeds” are usually caraway. The Folger Shakespeare Library offers a recipe for seed cake based off a recommendation by poet Thomas Tussore, in his 1573 Five Hundred Points of Good Husbandry. He advises that seed cakes be made after the sowing season and harvest. These cakes would have been given to workers for supper, or even dipped in ale. Some of the medieval references to seed cakes do not contain seeds at all – the name was only a reference to the ‘seed-time’ in which it was eaten. The Oxford Companion to Food notes that the cakes that did contain them would have seen it in the form of caraway comfits, coated in hard sugar, not merely the seed, which was an 18th-century development.

Recipes for seed cake are included in A.W.’s A book of cookrye Very necessary for all such as delight therin (1591) and Gervase Markham’s English Huswife (1615). Both Hannah Glasse, in The Art of Cookery, offers a “rich” version, also called a Nun’s cake, possibly due to “the era in Britain when the rewards of monastic life included the baking and eating of rich cakes,” according to Fitzgerald & Stavely in Northern Hospitality, which contains ambergris. Two more notable seed cake recipes are documented by Eliza Smith and Isabella Beeton. In terms of ingredients, more economical seed cakes used yeast, and richer ones used eggs. Variations included the common addition of rosewater, orange flower water (vanilla extract would be the modern substitute for these two), brandy, spices like cloves, mace, nutmeg, allspice and ginger, saffron, candied peel, and dried fruit.

Ballymena Weekly Telegraph, 18 June 1898

Outside of England, seed cake was popular in Ireland and Wales, especially at tea time and during the Christmas season. As reported in the Dublin Gazette in 1754, poisoned seed cakes were accidentally eaten by a few children and two servants (they survived, and the poisoner, who sent a warning letter, was not found). In 1837, Michael Delany stole two christening cakes and one seed cake, worth “nine or ten shillings”, from Thomas Trottere of Capel-street. Incriminating crumbs were found on his person, and the “old offender,” a mere twelve years old, was sentenced to a year’s hard labor. Seed cakes were advertised by bakers in Irish papers as early as 1838, and an 1847 ad seeking a maid in Dublin required that she “understand” seed cake.They seemed to have reached their peak in Ireland from 1860-1890. However, they fell out of favor in the 1900s – the taste of caraway can often be dividing. They were dismissed as out of date by the Belfast Telegraph in 1962. However, Mary Guckian’s Perfume of the Soil (1999), a nostalgic journey through rural Ireland, recalls visits from the eggler, and that his seed cakes were sold out by the time he traveled the four miles from town to her home in Co. Leitrim.

An Unexpected Seed Cake

Seed cake has a rich literary tradition. It appears in Jane Austen’s Jane Eyre (“she got up, unlocked a drawer, and taking from it a parcel wrapped in paper, disclosed presently to our eyes a good-sized seed-cake”), Charles Dickens’ David Copperfield (“I cut and handed the sweet seed-cake – the little sisters had a bird-like fondness for picking up seeds and pecking at sugar”), and in works by Charlotte Brontë and Agatha Christie. Perhaps the most famous appearance of seed cake in literature, and my favorite, is in J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit. Tolkien drew much inspiration for the Shire from village life in the Victorian English countryside, so the scene in “An Unexpected Party”, or at least its edibles, would have been familiar to many of his readers.

A little beer would suit me better, if it us all the same to you, my good sir,” said Balin with the white beard. “But I don’t mind some cake – seed-cake, if you have any.” “Lots!” Bilbo found himself answering, to his own surprise; and he found himself scuttling off, too, to the cellar to fill a pint beer-mug, and to the pantry to fetch two beautiful round seed-cakes which he had baked that afternoon for his after-supper morsel.

James Joyce utilizes seed cake in a more modern, sensual context in Ulysses, which I’ll not repeat here.

A tradition that was popular in Galway, as well as other areas, was for a cake or bread to be broken above the heads of a newly married couple by a married woman, usually the bride’s mother-in-law, so they would not want for food in their new life. While oat bread was often used, seed cake sometimes made an appearance – the scraps would be collected and slept on for luck.

Caraway Seed Cake Recipe

From Darina Allen’s Irish Traditional Cooking.

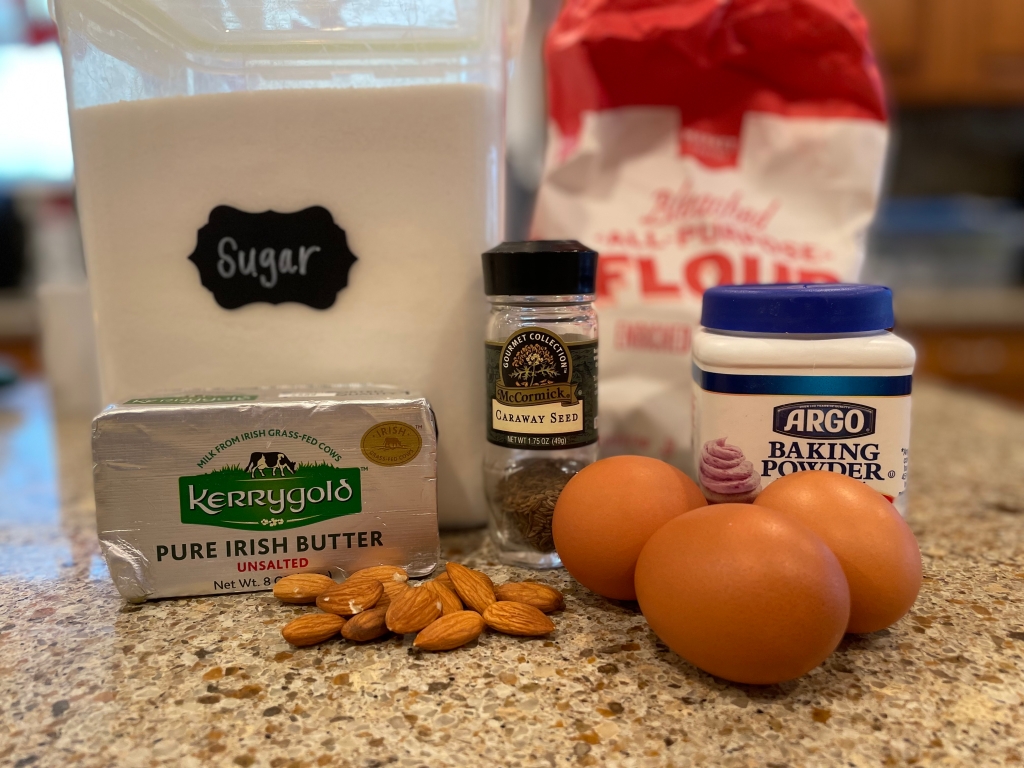

INGREDIENTS

12 tablespoons (1 ½ sticks) butter

1 cup superfine granulated sugar (you can use regular sugar granulated sugar, or whiz in food processor if you have one)

3 eggs

2 cups flour

1 tablespoon ground almonds (optional)

1 ½ tablespoons caraway seeds

¼ teaspoon baking powder

some caraway seeds to sprinkle on top

METHOD

1. Preheat oven to 350°F/180°C/gas mark 4 and line a tin with parchment paper.

2. Cream butter and sugar until light and fluffy. Gradually beat in eggs.

3. Stir in flour and ground almonds. Add caraway seeds and baking powder.

4. Pour into prepared tin, sprinkle seeds on top and bake for 50 to 60 minutes.